The Loss of The IOLAIRE

“ No one now alive in Lewis can ever forget the 1st of January 1919 and future generations will speak of it as the blackest day in the history of the island, for on it 200 of our bravest and best perished on the very threshold of their homes under the most tragic circumstances.”

So wrote William Grant of the Stornoway Gazette.

THE IOLAIRE YACHT 1881-1919

At about 0150 on the morning of Wednesday 1st January 1919 Her Majesty’s Yacht IOLAIRE ran aground on the Beasts of Holm at the entrance to Stornoway harbour on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Two hundred and fifty men were lost, only seventy-five were saved.

At around 1930 on the evening of 31st December 1918 HMY IOLARE sailed from the Kyle of Lochalsh to Lewis with servicemen on leave. Their families, friends and sweethearts were waiting for them at Stornoway or at their homes on Lewis and Harris but many of the men were destined never to see them again: an appalling tragedy of devastating proportions. Fifty-six bodies were never recovered.

The men, many of them Royal Navy Reservists, were coming home on leave from Plymouth and Portsmouth by train to Inverness and then on to Kyle. It was apparent to those organising the return that the regular MacBrayne ferry, Sheila would not be able to take them all and so the Royal Navy’s Stornoway Depot ship HMY IOLAIRE (formerly the Amalthea) was dispatched to Kyle to assist.

The first train arrived at Kyle at 1815 and the second at 1900. Three hundred and twenty libertymen disembarked. Sheila took thirty of them and the balance, two hundred and ninety – all naval ratings – were crowded onto the IOLAIRE, which was overloaded. No names were recorded so there were no passenger lists. At 1930 the lines were cast off. The Sheila would sail half an hour later.

Neither Commander Mason, the Captain, nor Lieutenant Cotter, the Navigating Officer, had taken a vessel into Stornoway at night. Neither of them survived.

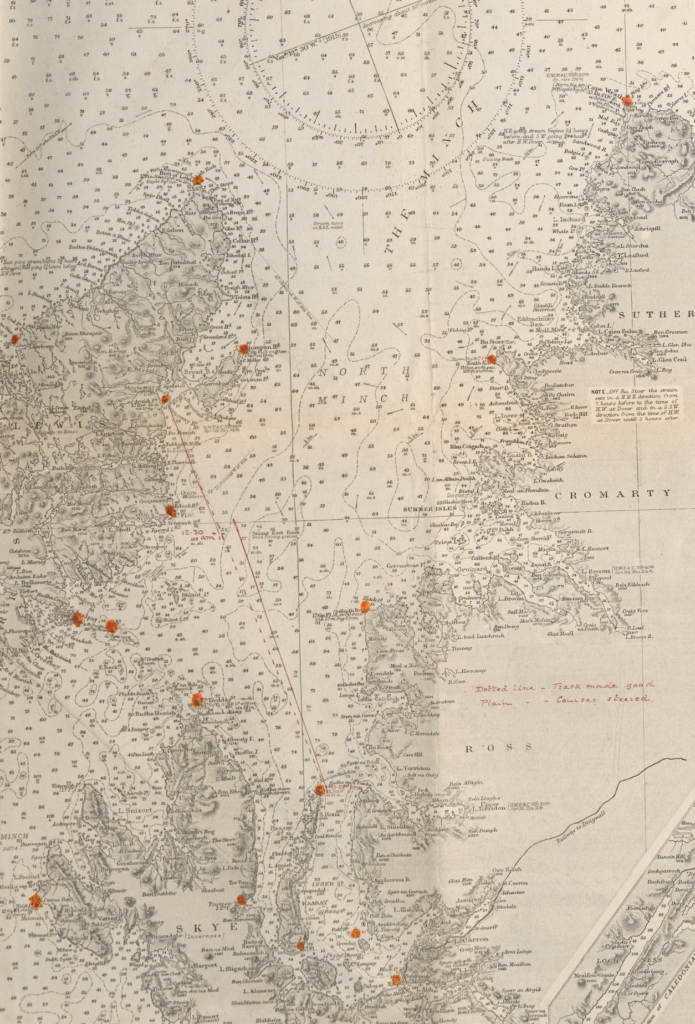

By 2155 the IOLAIRE should have cleared Rona Light at her normal speed of ten knots and would have been heading out into the Minch from the Sound of Raasay on a northerly course for the forty mile passage to Stornoway. From midnight the wind freshened from the south with intermittent squalls. From the testimony of the helmsman, James McLean – on the wheel from 2359 to 0100 – “lights could be seen quite distinctly”. At 0100 Lieutenant Cotter, took the watch from Commander Mason who went down to his cabin. And the helmsman changed.

When James McLean took the wheel at 2359 she was on a “north-easterly course – just a touch easterly” and making good about two degrees east of North. At 0030 course was altered to North.

For most of the passage the wind was reported to have been from astern with very little motion but it increased in force as they approached Lewis and there was a heavy sea running according to the skipper of the fishing vessel Spider.

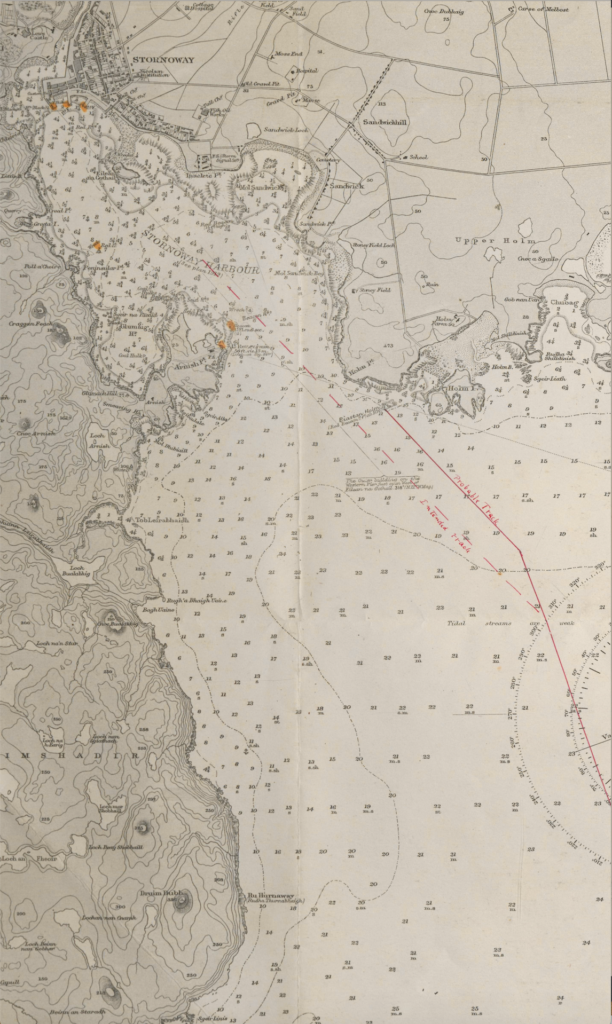

James McLean could see the light at Arnish Point about half a point on the port bow. What happened after that is unclear except that she entered the approaches to Stornoway too far to the east. Some witnesses on deck reported that they could see the shore far too close to the ship and two witnesses stated that in the five to ten minutes before she struck there was a change in the motion of the ship, which would have been as a result of a bold alteration to port bringing the sea onto the port beam. James MacDonald, skipper of the fishing vessel Spider, which had been overtaken by the IOLAIRE opposite the entrance to Lock Grimashadar (just over two miles south of the Beasts of Holm), stated in his testimony that, “I noticed that the vessel did not alter her course… but kept straight on in the direction of the Beasts of Holm. I remarked to one of the crew that the vessel would not clear the headland at Holm ….”

Moments later at about 0150 the IOLAIRE struck the Beasts of Holm – a remote location on the eastern side of the approaches to Stornoway and found herself between them and the rocky shore being pounded by large waves in total darkness and listing heavily to starboard. Fifty or sixty men were pitched into the sea immediately and were lost. A few managed to jump to safety as the stern swung into the shore. Distress rockets were sent up – fired by Cdr Mason – and the sirens sounded. Witnesses reported that no orders were ever issued from the Bridge.

As the ship settled she swung beam on to the shore which was about twenty yards away. John Finlay MacLeod, aged 32, braving the cold and the rocks swam ashore with a heaving line by means of which a hawser was pulled ashore and made fast but required backing up by men who made it to land. It was reported that thirty – forty men got ashore by this means. Some who tried couldn’t hold on. “Mountainous waves” were rolling over the ship and shortly afterwards she toppled over to port, the hawser was lost and the ship disappeared leaving only her masts showing.

About 0300 one survivor made it to the only habitation nearby, Stoneyfield farmhouse, and alerted the owners to the disaster.

The loss of two hundred and five men that morning was a devastating tragedy for the families and friends waiting ashore to greet them. Many villages lost all the menfolk of that generation and many of the women never married.

How did it happen?

A Court of Inquiry was held on 8th January 1919. It reported that, “From the evidence there appears to be nothing to account for the disaster. None of those on watch on the Bridge (the wheelhouse was on the deck below) at the time are survivors.”

What is irrefutable is that the IOLAIRE was too far to the east of her intended track as she approached the entrance to Stornoway harbour. So how could that have happened?

- Was it simply a failure to plot the ship’s track properly, although wind and tide were probably not significant factors because both were from the south (astern). In the days before radar there were few fixing marks at night, so initially Lt Cotter would have used dead-reckoning to plot his position.

- Was it because the planned track initially used Tiumpan Head light as the leading mark rather than Arnish Point light and she wheeled over to North too late.

- Did she alter course to starboard (to the east) to increase the range from the fishing vessel Spider, also heading for Stornoway who she was overtaking and then failed to alter back to port.

From the Director of Navigation’s reconstruction of events, having read the testimony of the witnesses, after the northern point of South Rona was cleared at about 2155 – assuming she was proceeding at her normal speed of ten knots – course was altered to North 2 degrees East (not clear how he could be certain about this given the lack of evidence – charts or witnesses. Helmsman James McLean’s evidence was from 2359.) and then at 0030 altered to North which was maintained until very shortly before the stranding. But the correct course from South Rona to Arnish Light at the entrance to Stornoway harbour was North 7 degrees West. Was Cdr Mason initially running on Tiumpan Head Light, the most easterly point of Lewis? Neither light, with nominal ranges of 13 and 19 miles respectively, would have been visible until the vessel was well into the Minch.

CHART OF THE PASSAGE:

Chart of the Passage

Chart of the entrance to Stornoway

But even if they were running on Tiumpan there would have been a planned alteration of course to port to run on Arnish Light. The wind was southerly, ie from astern and rising and the tidal stream from 2359 until she grounded was southerly. From the testimony of the only surviving helmsman, James MacLean, (who had the wheel from 2359 to 0100) at 0030 course was indeed altered to North and the Arnish Light was quite distinct half a point (about 5 degrees) on the port bow. This course was held until 0100 but what happened after that is unclear. In his evidence the Director of Navigation stated that “in the twelve mile run from that time [the alteration at 0030] the vessel appears to have been set about 6 cables to the Eastward.”

This would have in due course necessitated the major alteration of course to port, to the West, to bring the Arnish Light, marking the entrance to Stornoway ahead, and to avoid the Beasts of Holm, which were unlit.

Did Lt Cotter, who took over the watch at 0100, make an error in plotting his track or was he not fixing his position regularly and wheeled over to North late – hence the six cable error – distracted by the passengers on the crowded bridge.

The Master of the Sheila was asked if Stornoway was a difficult harbor to enter at night. He replied, “Well it is for the man that does not know it.”

The Inquiry summarised its findings thus:

‘The cause of the accident seems to have been that finding himself to the eastward of his intended position, the Commanding officer [sic] altered course to pass close to Arnish beacon light but, owing to the angle at which he was approaching the harbour, this track led him close to Holm Point; being further from Arnish point [sic] light than he estimated…instead of clearing Holm Point the ship ran on to Biastan Holm reef [The Beasts].’

And added that;

‘the Officer in Charge … did not exercise sufficient prudence in approaching the harbour.’

The Iolaire Disaster Fund was set up almost immediately.

It wasn’t until 1960 that a modest monument was put up to commemorate the loss, such was the searing impact on the loss on communities in Lewis and Harris.

Commodore Malcolm Williams, Former Chief Executive, Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society.